When you first notice your hand trembling while resting, or that your handwriting has gotten smaller over time, it’s easy to brush it off as just aging. But for many people, these subtle changes are early signs of something more serious: Parkinson’s disease. It’s not just about shaking hands. It’s about losing the ability to move freely, speak clearly, or even swallow safely. And while there’s no cure yet, knowing what to expect - and how to manage it - can make a huge difference in staying independent longer.

What Are the Core Motor Symptoms?

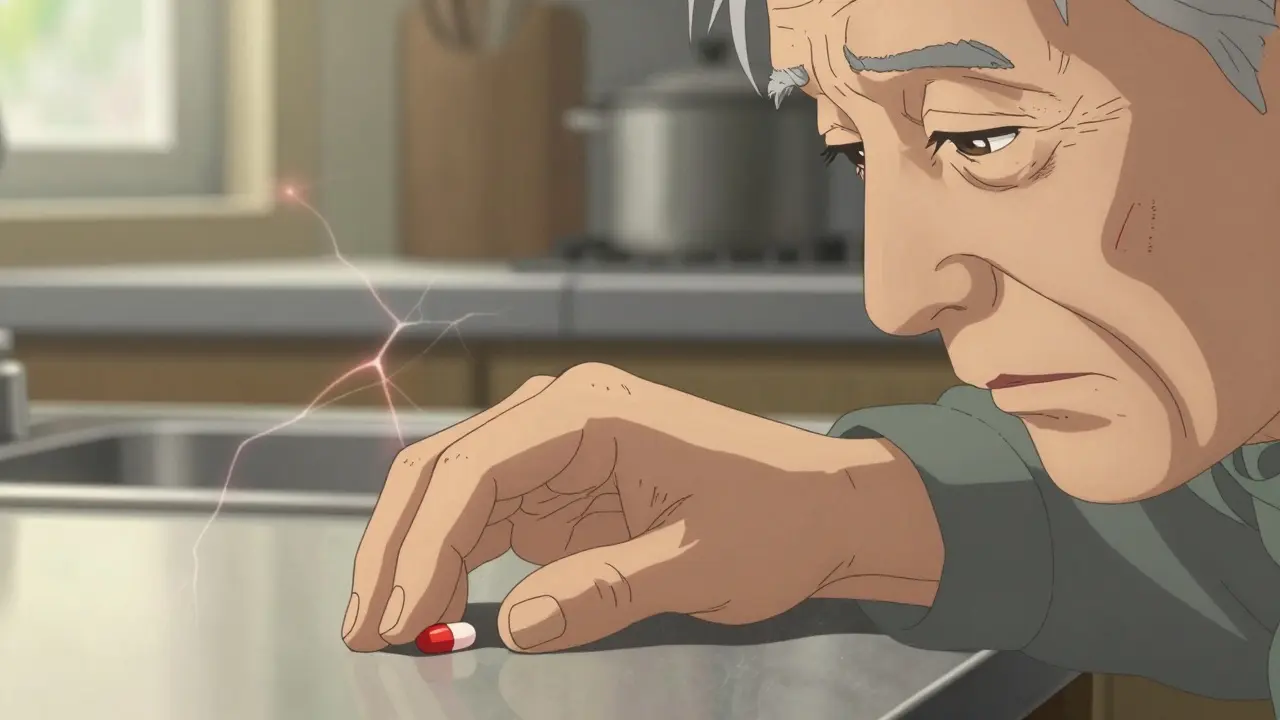

Parkinson’s disease attacks the brain’s ability to produce dopamine, a chemical that helps control movement. Without enough dopamine, signals between the brain and body get scrambled. That’s why four main motor symptoms show up, and doctors use them to diagnose the condition:- Tremor: Often starts in one hand as a slow, rhythmic shaking - like rolling a pill between your thumb and finger. It happens mostly when you’re not moving. About 70% of people notice this first, but 20-30% never develop noticeable tremors.

- Rigidity: Muscles feel stiff, like bending a lead pipe. Sometimes it’s uneven - a jerky resistance called cogwheel rigidity - which happens in 85% of cases. This stiffness can make turning in bed or getting out of a chair feel impossible.

- Bradykinesia: This means slow movement. It’s not just taking longer to do things; it’s like your body forgets how to start. Facial expressions flatten, blinking slows, and simple tasks like buttoning a shirt take three times longer. This symptom is present in nearly every patient, often before tremors appear.

- Postural instability: Balance problems come later, usually after 5-10 years. You might lean forward, stumble easily, or fall without warning. About 68% of people with Parkinson’s fall at least once a year.

These aren’t just annoyances - they’re the foundation of diagnosis. Doctors don’t need all four. But they do need bradykinesia plus at least one other. That’s because tremor can be misleading - it’s common, but not universal.

What Other Motor Signs Should You Watch For?

Beyond the big four, Parkinson’s brings a long list of smaller but equally disruptive changes:- Reduced arm swing: When you walk, one or both arms don’t swing naturally. This happens in up to 75% of people and throws off balance.

- Stooped posture: Shoulders hunch forward. About two-thirds to four-fifths of patients develop this over time.

- Micrographia: Handwriting gets smaller and more cramped. You might not even notice it until someone points it out.

- Soft or slurred speech: Voice volume drops by 5-10 decibels - enough to make conversations frustrating. About 89% develop a quiet voice; 74% struggle with slurring.

- Drooling: Not because you’re producing more saliva, but because swallowing slows down. Half to 80% of people experience this.

- Dysphagia: Trouble swallowing can lead to choking or pneumonia. In advanced stages, up to 80% face this risk.

- Dystonia: Involuntary muscle contractions twist limbs or the neck. More common in younger patients.

These symptoms creep in slowly. One day, you realize your socks won’t pull on easily. The next, you’re avoiding social dinners because you can’t speak loudly enough. These aren’t just physical - they’re emotional. Losing control over your body is one of the hardest parts of living with Parkinson’s.

How Are Medications Used to Manage Symptoms?

There’s no drug that stops Parkinson’s from progressing. But there are medications that help you live better while it does.Levodopa is still the gold standard. It’s converted into dopamine in the brain and helps restore movement. About 70-80% of people see big improvements at first. But after five years, about half develop side effects: unpredictable “on-off” swings where the medicine works well one minute and barely at all the next, and dyskinesias - involuntary, dance-like movements.

To delay those side effects, especially in younger patients, doctors often start with dopamine agonists like pramipexole or ropinirole. These mimic dopamine’s effects. They’re less powerful than levodopa, helping about 50-60% of early-stage patients. But they can cause nausea, dizziness, and even impulse control problems - like gambling or overeating.

Other options include MAO-B inhibitors (like selegiline) and COMT inhibitors (like entacapone), which help levodopa last longer. Anticholinergics may help tremor in younger patients but are avoided in older adults due to memory side effects.

For those who’ve been on levodopa for 10+ years and aren’t responding well anymore, deep brain stimulation (DBS) surgery is an option. About 30% of long-term patients eventually get it. Electrodes are placed in specific brain areas to send electrical pulses that smooth out movement. It doesn’t cure Parkinson’s, but it can cut medication doses by half and reduce tremors and dyskinesias.

How Does Parkinson’s Change Daily Life?

Daily routines that once felt automatic become battles:- Dressing: Buttoning shirts, zipping pants, tying shoes - all take longer. Studies show dressing takes 2.3 times longer than for healthy peers.

- Walking: Steps get shorter, speed drops by 30-40%. Many people shuffle. Turning becomes risky - you might need multiple small steps instead of one smooth pivot.

- Getting out of bed: About 65% of people struggle to turn over or sit up without help.

- Eating: Drooling and swallowing problems mean meals are stressful. Some need thickened liquids or pureed food. Aspiration pneumonia, caused by food or liquid entering the lungs, is the leading cause of death in advanced Parkinson’s.

- Communication: Speaking softly or slurring words makes phone calls, group chats, and even family dinners exhausting. People often misinterpret silence as disinterest.

- Sexual health: Up to 80% of men report reduced libido or erectile dysfunction. It’s rarely discussed but deeply affects relationships.

- Sleep: Restless legs, vivid dreams, or sudden muscle movements during sleep are common. Some develop akathisia - an inner restlessness that makes sitting still impossible.

These aren’t just inconveniences. They chip away at independence. Many people stop going out, stop cooking, stop socializing - not because they don’t want to, but because they can’t do it safely or comfortably anymore.

What Non-Medication Strategies Help?

Medications don’t fix everything. But movement, therapy, and support can slow decline and rebuild confidence.- Physical therapy: Targeted exercises improve balance, walking speed, and strength. One study showed 12 weeks of therapy increased walking speed by 15-20% and cut falls by 30%.

- Speech therapy: Programs like LSVT LOUD help people speak louder and clearer. Many regain enough voice volume to be understood in noisy rooms.

- Occupational therapy: Helps adapt the home - installing grab bars, using button hooks, switching to slip-on shoes, or using voice-activated devices.

- Exercise: Dancing, tai chi, cycling, and even boxing classes have been shown to improve mobility and mood. Movement isn’t just therapy - it’s medicine.

- Support groups: Talking with others who get it reduces isolation. You learn practical tips: how to fall safely, what shoes work best, where to find adaptive utensils.

These aren’t add-ons. They’re essential. People who stay active, socially connected, and engaged in therapy maintain independence longer than those who rely only on pills.

What’s the Long-Term Outlook?

Parkinson’s doesn’t kill directly. But its complications do. As the disease progresses, swallowing problems, falls, and infections become life-threatening. The Hoehn and Yahr scale describes five stages - from mild symptoms on one side of the body to full disability requiring constant care.Progression is slow. It can take 5 to 20 years to reach advanced stages. But early diagnosis and consistent management make all the difference. The goal isn’t to stop the disease - it’s to keep you moving, speaking, eating, and living as long as possible.

Right now, no medication has been proven to slow Parkinson’s progression. But research is accelerating. New drugs targeting alpha-synuclein - the protein that builds up in the brains of people with Parkinson’s - are in clinical trials. The hope isn’t just better symptoms. It’s a future where Parkinson’s is managed like diabetes: controlled, predictable, and not life-limiting.

Can Parkinson’s be cured?

No, there is no cure for Parkinson’s disease yet. Current treatments focus on managing symptoms to improve quality of life. Medications like levodopa help restore movement, and therapies like deep brain stimulation can reduce motor fluctuations. Research is ongoing, especially into drugs that target alpha-synuclein, but no therapy has been proven to stop or reverse the disease process.

Is tremor always the first sign of Parkinson’s?

No. While tremor is the most common symptom at diagnosis - affecting about 70% of people - 20-30% never develop noticeable shaking. The most reliable early sign is bradykinesia, or slow movement. This includes reduced facial expression, smaller handwriting, or difficulty starting movements like standing up or walking. Doctors rely on bradykinesia plus either tremor or rigidity to make a diagnosis.

Why does levodopa stop working well after a few years?

Levodopa doesn’t stop the brain from losing dopamine-producing cells - it just replaces what’s lost. Over time, as more cells die, the brain can’t store or use levodopa as efficiently. This leads to “on-off” fluctuations, where the medicine’s effects wear off unpredictably, and dyskinesias - uncontrolled movements - appear. These side effects affect up to 50% of patients after five years of treatment. Doctors adjust doses or add other drugs to manage this, but it’s a natural part of disease progression.

Can exercise really help with Parkinson’s symptoms?

Yes, and strongly so. Studies show that regular, targeted exercise improves balance, walking speed, and strength. People who do 150 minutes a week of aerobic activity, strength training, or activities like tai chi or dancing reduce their fall risk by 30%. Exercise may even help protect remaining dopamine neurons. It’s not a replacement for medication - but it’s one of the most effective tools for maintaining independence.

When should someone consider deep brain stimulation (DBS)?

DBS is typically considered after 4-10 years of Parkinson’s, when medications no longer provide stable symptom control. Signs include frequent “off” periods, severe dyskinesias, or tremors that don’t respond to drug adjustments. It’s not for everyone - patients need to be in good general health, have a clear diagnosis, and respond well to levodopa. About 30% of long-term patients eventually get DBS, and many report a major improvement in daily function.

What’s the biggest threat to life in advanced Parkinson’s?

The biggest threat isn’t the disease itself, but its complications. Difficulty swallowing (dysphagia) leads to aspiration pneumonia - when food or liquid enters the lungs. This causes infection and accounts for about 70% of Parkinson’s-related deaths in advanced stages. Falls, infections, and dehydration also contribute. Managing swallowing with speech therapy, adjusting food textures, and staying hydrated are critical for survival.

What Comes Next?

If you or someone you care about is newly diagnosed, the first step isn’t panic - it’s planning. See a neurologist who specializes in movement disorders. Start physical therapy. Talk to a speech therapist. Join a support group. These aren’t optional extras - they’re part of the treatment plan.Medications help you move. Therapy helps you live. And staying connected - to people, to routines, to purpose - keeps you human.

Parkinson’s changes your body. But it doesn’t have to change who you are. With the right support, many people live full, active lives for decades after diagnosis. The goal isn’t to fight the disease. It’s to live well inside it.

kumar kc

January 18, 2026 AT 15:05People need to stop treating Parkinson’s like it’s just ‘getting old.’ This isn’t normal aging-it’s a neurological breakdown. If you’re shaking, slow, or dropping things, get checked. Not tomorrow. Today.

Thomas Varner

January 20, 2026 AT 03:26Man... I didn’t realize how many little things add up-like not swinging your arms while walking, or how your handwriting just... shrinks. I watched my dad go through this. He never said much, but I’d catch him staring at his hand like it betrayed him. It’s the quiet stuff that kills you. 😔

Art Gar

January 20, 2026 AT 21:02It is incumbent upon the lay public to recognize that the medicalization of aging-related motor phenomena constitutes a dangerous overdiagnostic trend. The diagnostic criteria for Parkinson’s disease, as presented herein, are not sufficiently specific to warrant population-wide alarmism. Moreover, the emphasis on pharmacological intervention neglects the epistemological limitations of dopaminergic replacement therapy.

Edith Brederode

January 22, 2026 AT 08:39This is so important to share 💙 I’ve seen friends go through this and it’s heartbreaking how isolated they feel. The speech therapy and dancing part? YES. My aunt did LSVT LOUD and suddenly she was laughing again at dinner. It’s not magic, but it’s hope. 🙏

Emily Leigh

January 22, 2026 AT 11:15So… we’re just supposed to believe every single one of these stats? 89% have quiet voices? 74% slur? Who measured this? Did they use a decibel meter in a Walmart? I’m skeptical. Also, ‘boxing classes help’? Like, Mike Tyson boxing? 😅

thomas wall

January 24, 2026 AT 00:03The tragic erosion of autonomy in Parkinson’s patients is not merely a clinical phenomenon-it is a moral indictment of a healthcare system that prioritizes pharmacological band-aids over holistic dignity. The absence of a cure is not an accident; it is the consequence of institutional neglect.

pragya mishra

January 24, 2026 AT 06:30My uncle had this. He stopped eating because he was scared of choking. No one told him about thickened liquids. He died in a hospital with a feeding tube. You people need to stop writing articles and start telling families what to DO. Not just ‘therapy helps’-tell us HOW to find it. Where? Who pays?

Andy Thompson

January 24, 2026 AT 14:35Levodopa? DBS? HA. They’re all just cover-ups. The real cause? Fluoride in the water. Glyphosate in your bread. The WHO knows. The FDA hides it. You think they’d let a cure exist? Nah. Bill Gates wants you dependent on pills. Watch the documentary ‘Parkinson’s: The Silent Poison’-it’s on BitChute.

sagar sanadi

January 25, 2026 AT 02:28So dopamine is the problem? Funny… I take coffee every morning. That’s dopamine, right? So why am I not walking like a robot? Maybe the real problem is… you’re all just too lazy to move. 🤷♂️

Arlene Mathison

January 25, 2026 AT 14:54MOVE. MOVE. MOVE. I don’t care if you’re 60 or 80-dance in your kitchen. Walk around the block. Ride a bike. Even if it’s slow. Your brain NEEDS it. I’ve seen people who started at stage 2 and now they’re hiking. It’s not a miracle-it’s science. You’ve got this. 💪❤️

Jacob Cathro

January 27, 2026 AT 12:40Levodopa’s pharmacokinetics are a mess-non-linear absorption, erratic plasma half-life, and peripheral decarboxylation inefficiencies. Add in blood-brain barrier permeability issues, and you’ve got a therapeutic nightmare. Meanwhile, dyskinesias are just the CNS screaming ‘I’m overstimulated!’-yet we keep doubling down? Pathetic.

Paul Barnes

January 28, 2026 AT 17:07The article is well-researched and accurately cites peer-reviewed prevalence rates. However, the omission of non-motor symptoms such as REM sleep behavior disorder and hyposmia as early diagnostic markers is a significant oversight.

Carolyn Rose Meszaros

January 30, 2026 AT 09:00My grandma got diagnosed at 72. She started tai chi with a group of other seniors. Now they meet every Tuesday. They don’t talk about Parkinson’s. They talk about their grandkids, their cats, and who brought the best cookies. That’s the real medicine. 🌸

Greg Robertson

January 31, 2026 AT 18:32Thanks for writing this. My dad’s in stage 3 and I’ve been clueless. This helped me understand why he won’t shake my hand anymore-not because he’s mad, but because he can’t control it. I’ll get him into PT this week. 🙏