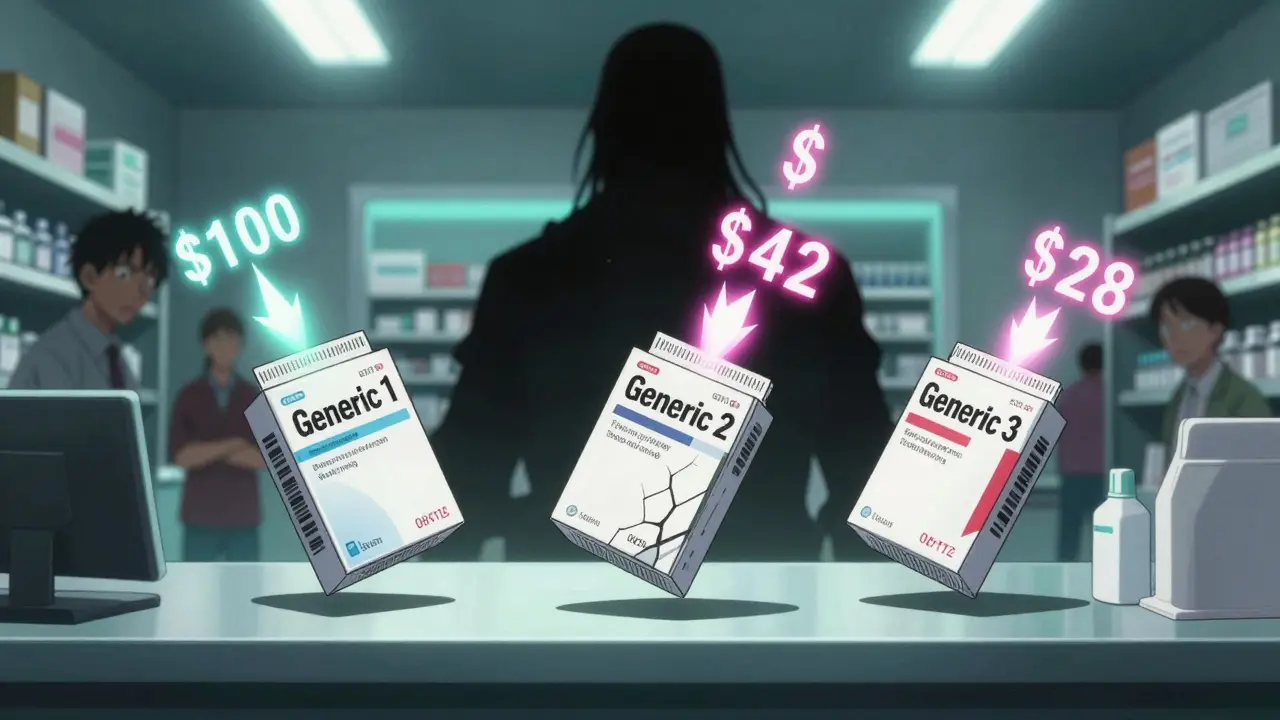

When a brand-name drug loses its patent, the first generic version usually hits the market at about 15% to 20% of the original price. That’s a big drop. But here’s what most people don’t realize: the real savings come after that first generic. When a second company starts making the same drug, prices plunge again. By the time a third maker joins, the price often drops to less than half of what the brand charged - sometimes even lower.

Why the second generic changes everything

The first generic drug maker doesn’t have much pressure to cut prices. They’re the only game in town. So they charge what they can get away with - usually around 87% of the brand’s price. But once a second company enters, everything shifts. Suddenly, there are two suppliers fighting for the same customers. Pharmacies, insurers, and hospitals start playing them off each other. The second company needs to undercut the first to win business. That forces the first company to lower its price too. The result? Prices drop to about 58% of the brand’s original cost. That’s a 31% drop from the first generic’s price - just from adding one more competitor.The third generic hits the sweet spot

Add a third manufacturer, and the price doesn’t just dip - it crashes. On average, the third generic brings the price down to just 42% of the brand’s original price. That means patients and insurers are paying less than half of what they paid when the drug was still under patent. In some cases, especially for high-volume drugs like statins or blood pressure pills, prices drop even further - to 30% or less. The FDA found that when three or more companies make the same generic drug, prices fall by 27% more than they did between the brand and the first generic. That’s not a small bump. That’s life-changing savings for people on fixed incomes or taking multiple medications.More competitors = bigger savings

It doesn’t stop at three. When five or more companies make the same generic drug, prices can fall to just 10-20% of the brand’s original price. Markets with 10 or more generic manufacturers often see price reductions of 70-80% compared to the brand. These aren’t theoretical numbers. In 2022, the FDA reported that the 2,400 new generic drugs approved between 2018 and 2020 saved U.S. consumers $265 billion. Almost all of that came from the ripple effect of multiple competitors entering the market. The more companies making the drug, the harder they have to fight to keep their share - and that fight is what keeps prices low.

What happens when competition fades

But here’s the dark side: if one of those manufacturers leaves the market, prices can spike. A University of Florida study found that when a market drops from three generic makers to just two, prices often jump by 100% to 300%. That’s not a mistake. It’s a business strategy. With fewer players, the remaining companies can quietly coordinate pricing - no need to undercut each other anymore. This is why duopolies (two makers) are dangerous. Nearly half of all generic drug markets in the U.S. are stuck in this state, missing out on the deep discounts that come with real competition. The same study showed that when a third maker finally enters a duopoly, prices drop an average of 36% in just a few months.Why aren’t there more generic makers?

You’d think more companies would jump in when prices are high. But it’s not that simple. Making a generic drug sounds easy - it’s the same chemical as the brand. But getting FDA approval takes years and millions of dollars. For complex drugs - like inhalers, injectables, or topical creams - the cost can be over $10 million. Smaller companies can’t afford that risk. And even if they do get approved, they face a stacked system. Three big wholesalers - McKesson, AmerisourceBergen, and Cardinal Health - control 85% of the drug distribution network. Three major pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) - Express Scripts, CVS Health, and UnitedHealth’s Optum - decide which generics get covered and at what price. These middlemen have enormous power. They can favor the cheapest bid, but they can also punish manufacturers who don’t pay them kickbacks or refuse to give deep discounts. That makes it harder for new entrants to get shelf space.How anti-competitive tactics block savings

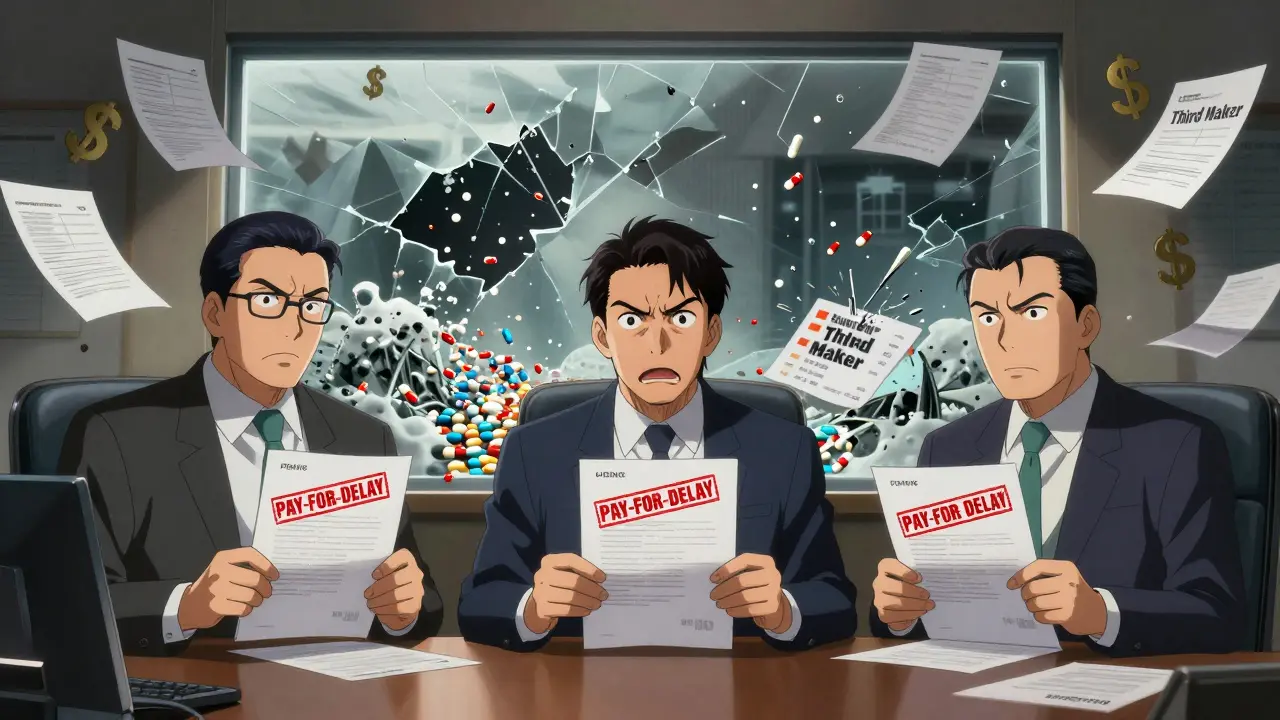

Sometimes, the brand-name company doesn’t wait for generics to enter. They pay them not to. These are called “pay-for-delay” deals. The brand pays a generic company millions to delay launching their version - sometimes for years. The Blue Cross Blue Shield Association estimates these deals cost patients $3 billion a year in higher out-of-pocket costs. In one case, a popular antibiotic had a generic version ready in 2014, but the brand paid the maker to wait until 2019. That’s five years of inflated prices. Congress has tried to ban these deals with bills like the Preserve Access to Affordable Generics Act, but they’re still happening. Another tactic is “patent thicketing” - where the brand files dozens of minor patents on packaging, dosing, or delivery methods to block generics. One drug had 75 patents, stretching its monopoly from 2016 all the way to 2034. That’s not innovation. That’s legal obstruction.

Meenakshi Jaiswal

December 20, 2025 AT 10:29I’ve been on a generic statin for years and never realized how much the number of manufacturers mattered. Switched to a different generic last year-same active ingredient, but three companies make it-and my copay dropped from $45 to $12. No joke. If you’re paying more than $20 for a common generic, ask your pharmacist if there’s another version. It’s not magic, it’s just competition.

Also, GoodRx saved me over $300 last year. Use it.

Thanks for this post. People need to know this stuff.

Connie Zehner

December 21, 2025 AT 04:16OMG I KNEW IT!! 😤 I’ve been saying this for YEARS!! The PBMs are ROBBING US!! They’re in bed with Big Pharma!! I saw a video on TikTok where a guy showed his PBM invoice and it had a $200 markup on a $3 generic!! 😱 They’re literally printing money off our prescriptions!!

And don’t even get me started on the FDA-they’re just puppets!! 🇺🇸💉 #PharmaCrimes #SaveOurPrescriptions

mark shortus

December 23, 2025 AT 04:03Okay so I just read this entire thing and I’m not even mad-I’m impressed. Like, I actually cried a little. This is the most important thing I’ve read since the time I found out my cat was allergic to tuna.

But also-can we talk about how the word ‘duopoly’ is spelled? It’s D-U-O-P-O-L-Y. Not ‘duopolly’. Not ‘duo-poly’. It’s D-U-O-P-O-L-Y. I’m not trying to be a grammar Nazi, but if you’re going to write about market structures, maybe learn the damn terminology?

Also, ‘sample hoarding’ is a real thing? I thought that was a plot from House M.D. 😭

Anyway. I’m going to change my blood pressure med. And I’m telling everyone. This is a public health emergency.

Edington Renwick

December 23, 2025 AT 10:41People don’t understand how broken this system is. It’s not about competition-it’s about control. The same four corporations own the PBMs, the wholesalers, and half the generic manufacturers. They’re not competing-they’re colluding under the guise of ‘market efficiency.’

And you think the FDA is helping? They approve generics but don’t monitor pricing. They don’t care if a drug goes from $1 to $120 because a competitor disappeared. They’re bureaucrats, not watchdogs.

This isn’t capitalism. It’s feudalism with a pharmacy counter.

Aboobakar Muhammedali

December 23, 2025 AT 15:32in india we have like 10 brands for the same blood pressure pill and most cost like 20 rupees a month... but here in the states... i dont even know how people afford it

my dad took a generic for 5 years and then one day it was gone... price jumped to 150 dollars... he just stopped taking it...

no one talks about this... but it kills people slowly

thank you for writing this

Laura Hamill

December 25, 2025 AT 11:42THEY’RE ALL IN ON THIS!! Big Pharma, PBMs, the FDA, the White House-they’re all part of the drug cartel!! I read a whistleblower report that said the CEO of Express Scripts owns a shell company that buys up small generic makers and then raises prices!!

And don’t tell me it’s ‘market forces’-it’s a rigged game!! We need to burn it all down!! 🚨🔥

Also, I heard the moon landing was fake. Same energy.

Nina Stacey

December 27, 2025 AT 06:25Wow this is so important i had no idea how much the number of manufacturers mattered

my sister just got diagnosed with high cholesterol and we were so worried about the cost but then we found out there are like seven different generics for atorvastatin and one of them is only 7 dollars a month at walmart

i told her to ask her doctor to switch and she was like ‘but isn’t that the same thing?’

and i was like honey no its not the same thing its the same chemical but different people making it and that changes everything

thank you for explaining this so clearly i’m sharing this with everyone i know

Dominic Suyo

December 28, 2025 AT 21:50Let’s be real: this isn’t about generics. It’s about the death of American capitalism. You’ve got a system where the only thing that matters is margin compression-except the margins are being compressed by people who don’t even have a seat at the table.

The real villains? The oligopolistic distribution network. McKesson, Cardinal, AmerisourceBergen-they’re not distributors, they’re gatekeepers with a monopoly on access.

And the PBMs? They’re not intermediaries-they’re rent-seekers with fiduciary duties to shareholders, not patients.

And yet, we’re supposed to be surprised when prices spike? This isn’t a market failure. It’s a market design failure. And nobody’s fixing it because the people who designed it are still running it.

Kevin Motta Top

December 30, 2025 AT 07:24Just came back from India last month. Same generic, same chemical, same FDA standards. In Delhi, it’s $0.20/month. In the U.S., it’s $40. No one’s talking about how the system is designed to extract wealth from the sick.

This isn’t about innovation. It’s about extraction.

Alisa Silvia Bila

December 31, 2025 AT 08:57I’m so glad someone finally explained this in plain terms. I’ve been confused for years why my pharmacy keeps switching my generic. Now I get it-they’re trying to get me on the cheapest one. But sometimes the cheapest isn’t the best for my insurance tier.

Thanks for the tip about checking how many makers there are. I just looked up my diabetes med-three makers. I didn’t even know that mattered.

Also, I’m going to start asking my doctor for alternatives with more generics. This feels like a small win I can actually control.

Danielle Stewart

January 2, 2026 AT 07:45This is one of the most important public health insights I’ve seen in years. I’ve worked in pharmacy for 17 years and I still get surprised by how little patients know about this.

People think ‘generic’ means ‘same price’-but no, it’s a dynamic market. More competitors = lower prices. Simple economics.

And yes, switching generics can save you hundreds. I’ve seen it. I’ve done it. I’ve told my own mother to switch her blood pressure med and she saved $80/month.

Don’t just take what’s on the shelf. Ask. Push. Compare.

You’re not being difficult-you’re being smart.

mary lizardo

January 2, 2026 AT 08:55While the data presented is statistically sound, the rhetorical framing is dangerously reductionist. The systemic failure is not merely a function of market competition, but of regulatory capture, intellectual property law distortion, and the commodification of health outcomes under neoliberal governance.

Furthermore, the suggestion that patients can ‘vote with their pharmacy’ is a neoliberal fantasy that ignores structural inequities in access, insurance coverage, and pharmaceutical literacy.

One cannot ‘opt out’ of a broken system when one’s survival depends on its functioning.

This post, while well-intentioned, dangerously implies agency where none exists.