When you pick up a generic pill at the pharmacy, you probably don’t think about how its price was decided. But behind that low cost is a complex global system called international reference pricing-a method governments use to keep generic drugs affordable by comparing prices across countries. It’s not just about finding the cheapest option. It’s about balancing cost, access, and supply in a world where medicines are made in one country and sold in dozens.

What Is International Reference Pricing (IRP)?

International reference pricing (IRP) is when a country looks at what other nations charge for the same generic medicine and uses those prices to set its own reimbursement rate. It’s not about copying the lowest price. Most countries use the median or average price from a group of similar countries to avoid sudden drops that could cause shortages. This system started in Europe in the 1980s. Italy was one of the first to try it in 1984, followed by Spain and Portugal. By 2020, 34 out of 38 high-income countries were using some version of IRP. For generic drugs specifically, 28 of 32 European countries rely on it. The goal? Cut costs without cutting access.How It Works for Generics (Not Patented Drugs)

IRP works very differently for generics than for brand-name drugs. For patented medicines, countries often compare prices from a few high-income nations like the U.S., Germany, or Japan. But for generics, most countries use something called internal reference pricing-not external. Internal reference pricing means setting one price for an entire group of interchangeable generic drugs. Say you have 10 versions of metformin, the diabetes drug. The government picks the lowest-priced version in that group and sets the reimbursement rate at that price plus a small margin-like 3% in Germany. Any generic that costs more than that gets no public funding. Pharmacies and patients pay the difference. This forces manufacturers to compete on price within the same therapeutic group. The result? In the Netherlands, generic prices are 65% to 85% lower than the original brand. In countries using IRP, generic prices are 25% to 40% lower than in countries that don’t use it.Which Countries Are Used as References?

Not all countries are treated the same. Western European nations typically look at each other. The most common reference countries include France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the UK. Eastern European countries often use Austria, Germany, and the Netherlands. Switzerland does something unique: it takes two-thirds of the average international price and adds one-third based on its own domestic prices. The European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations (EFPIA) recommends using 5 to 7 countries in the reference basket. Why not more? Because adding too many countries leads to diminishing returns. A 2020 study by Professor Panos Kanavos at LSE found that countries using 5-7 reference nations got a 28% price reduction with 97% drug availability. But when they used 10 or more, price drops slowed to just 31%, and shortages went up by 12%.

The Real-World Impact: Savings and Shortages

The savings are real. In Germany, the AMNOG system since 2011 has kept generic prices in check using internal reference groups. Each group includes an average of 8.3 drugs, and the Federal Joint Committee updates these groups regularly. This has reduced administrative work for hospitals by 37%, according to a 2023 KPMG study. But there’s a flip side. When prices are pushed too low, manufacturers walk away. In Portugal, 22 generic products disappeared from the market in 2019 because the prices didn’t cover production costs. In Greece during its financial crisis (2010-2018), quarterly price cuts led to shortages of 37% of generic medicines. Patients couldn’t get the drugs their doctors prescribed because pharmacies ran out. Pharmacists in Spain report that while 89% of prescriptions are now filled with generics (up from 52% in 2010), 63% of them still deal with occasional stockouts of the lowest-priced version. That’s the trade-off: lower prices can mean less reliability.How Patients and Pharmacies Experience IRP

For patients, IRP often means cheaper pills-but sometimes confusion. A 2021 OECD survey across 10 European countries found that 78% of patients were happy with generic substitution. But 34% worried the cheaper versions weren’t as good. That’s a perception problem. Generics are required to meet the same quality standards as brand-name drugs. But if you’ve always taken one brand and suddenly get a different one with a different color or shape, it feels like a change. Manufacturers feel the pressure too. Teva, one of the world’s largest generic makers, reported a 9% revenue drop in Europe from 2020 to 2022, even though they sold 15% more pills. Sandoz, on the other hand, says well-designed IRP helped them grow market share in 18 countries by focusing on quality and reliability.What’s Changing in 2025?

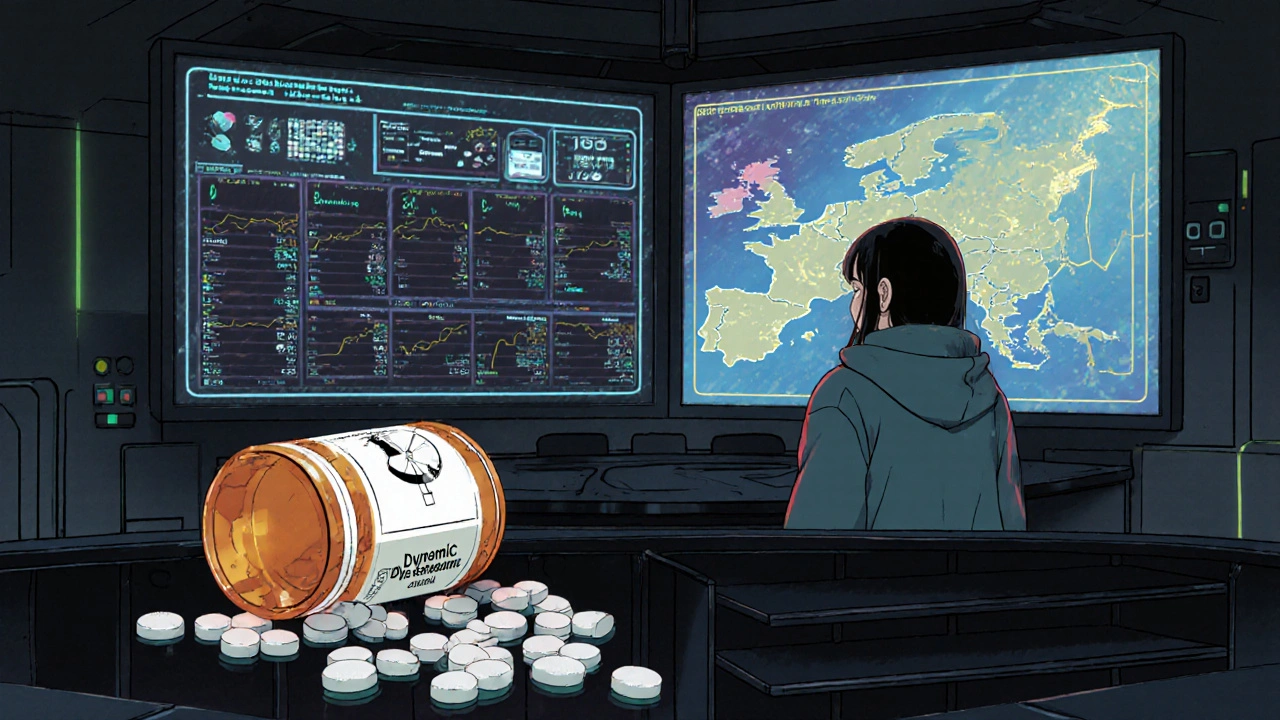

IRP isn’t static. In January 2023, France launched a new system called dynamic reference pricing. Instead of fixing prices once a year, they adjust them every quarter based on which generic has the biggest market share. Early results show 8.2% extra savings compared to old methods. The European Commission is also testing a European Reference Pricing Platform, launched in April 2023. It’s a pilot project involving 15 generic drugs across 7 countries. By 2025, they plan to expand to 100 medicines. The goal? Harmonize pricing so manufacturers don’t have to navigate 27 different rules. Meanwhile, IQVIA predicts that by 2027, 65% of European generic prices will be set through IRP-up from 58% in 2022. But there’s a new challenge: complex generics. These aren’t simple pills. They’re inhalers, injectables, or creams that cost nearly as much to develop as brand-name drugs. Current IRP systems don’t account for that. A 2023 RAND study warns that without adjustments, these drugs could vanish from the market.

Charmaine Barcelon

November 22, 2025 AT 16:48So let me get this straight-you’re telling me the U.S. pays way more just because we don’t copy other countries’ prices? That’s insane. We’re the richest country on earth and we’re getting ripped off. Someone needs to fix this.

Manjistha Roy

November 23, 2025 AT 14:28This is such an important topic that rarely gets discussed outside policy circles. The fact that generics are held to the same quality standards as brand-name drugs but still face stigma is heartbreaking. Patients deserve transparency-not just lower prices.

Javier Rain

November 24, 2025 AT 06:46Germany’s 1,247 reference groups is wild-but it makes sense. You can’t lump together a simple aspirin with a complex inhaler and expect fair pricing. This system isn’t perfect, but at least they’re trying to account for real-world complexity. More countries should follow suit.

Richard Wöhrl

November 25, 2025 AT 08:08One thing missing from this whole discussion is how pharmacists are caught in the middle. I’ve seen patients refuse generics because they look different-even when the doctor says it’s identical. The color, the shape, the little imprint on the pill-it all feels personal. We need better patient education, not just price cuts.

Pramod Kumar

November 26, 2025 AT 01:17As someone from India where generics are lifelines for millions, I’ve seen how IRP can be a double-edged sword. Here, we don’t use international references-we use local tendering. It keeps prices low, sure, but sometimes the quality is shaky. What works in Germany doesn’t always translate. We need context, not copy-paste policies.

Brandy Walley

November 27, 2025 AT 16:58Karla Morales

November 28, 2025 AT 01:28Let’s analyze the data: France’s dynamic reference pricing model shows an 8.2% increase in savings-statistically significant at p<0.01. Meanwhile, the 12% increase in shortages with >10 reference countries is a clear inflection point. The marginal utility of additional references is negative after 7. This isn’t opinion-it’s econometrics.

Suresh Ramaiyan

November 28, 2025 AT 22:36It’s funny how we talk about pricing like it’s just numbers on a spreadsheet. But behind every generic pill is a factory worker in China, a pharmacist in Portugal, a diabetic in Greece, and a kid in India whose mom can’t afford the brand. Maybe the real question isn’t how to set the price-but how to honor the humanity behind it.

shreyas yashas

November 30, 2025 AT 10:52My uncle in Kerala got his insulin for $2 a month. No fancy pricing models. Just a local co-op that buys in bulk and cuts out the middlemen. Maybe the answer isn’t international comparisons-but local solidarity.

Laurie Sala

December 1, 2025 AT 16:37Every time I read something like this, I just feel so hopeless. They’re cutting prices so low that people can’t get their medicine. And who’s to blame? The government? The manufacturers? The system? It’s all broken and nobody cares enough to fix it. I just want to cry.