Barrett’s esophagus isn’t a disease you can feel in the early stages. It doesn’t cause heartburn or pain on its own. But it’s the silent precursor to one of the deadliest cancers of the digestive tract: esophageal adenocarcinoma. If you’ve had chronic heartburn for more than five years - especially if you’re a man over 50, white, overweight, or a smoker - you’re at higher risk. And if you’ve been diagnosed with Barrett’s esophagus, the real question isn’t just whether you have it. It’s: What’s your risk of turning it into cancer, and what can you actually do about it?

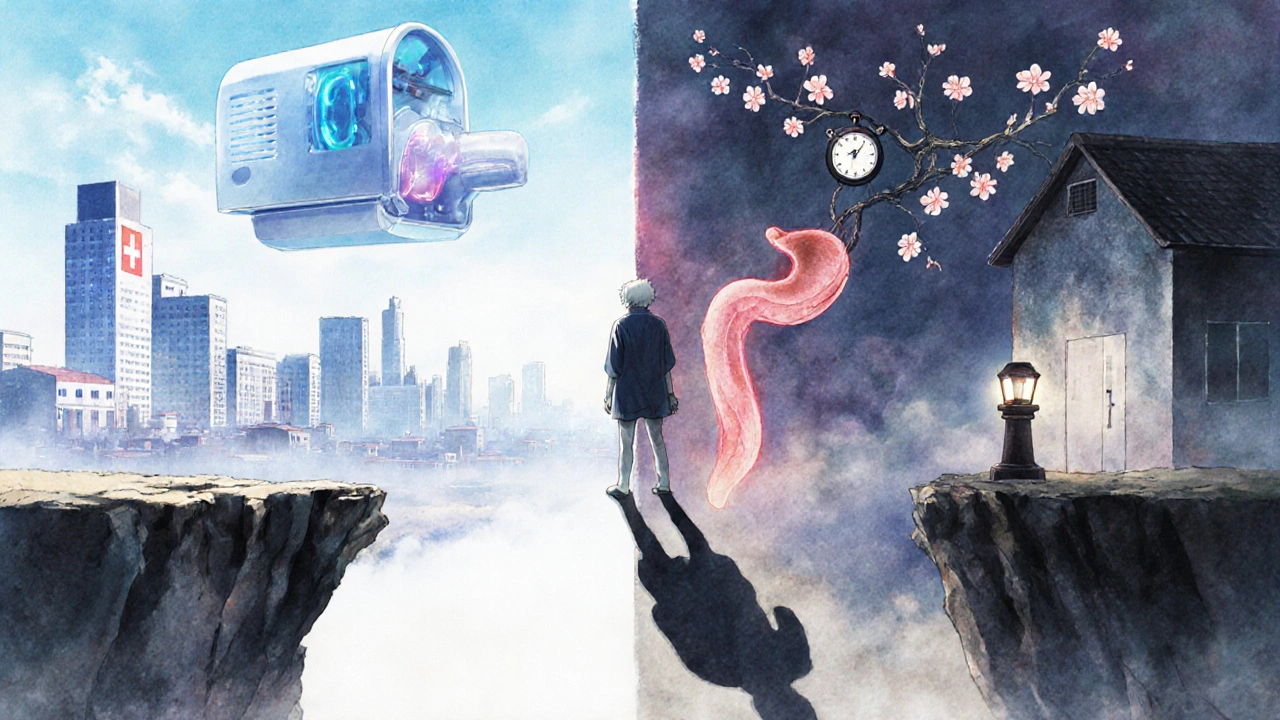

What Exactly Is Barrett’s Esophagus?

Barrett’s esophagus happens when the normal lining of your esophagus - the tube that connects your throat to your stomach - gets damaged by long-term acid reflux. Instead of the tough, pink squamous cells that should be there, your body replaces them with columnar cells that look more like the lining of your intestines. This change is called metaplasia. It’s your body’s attempt to protect itself from acid, but it comes with a dangerous trade-off.

This condition was first described in the 1950s, but it wasn’t until the 1970s that doctors realized it was linked to a rising tide of esophageal cancer. Since then, cases of this cancer have jumped more than 600% in Western countries. The good news? If caught early, survival rates jump from 20% to 80-90%. The catch? Most people don’t know they have Barrett’s until it’s advanced. That’s why screening matters - especially if you’re in a high-risk group.

Who’s Most at Risk for Progression?

Not everyone with Barrett’s esophagus will develop cancer. But some people are far more likely to. The biggest red flags are:

- Long-segment Barrett’s: If the abnormal tissue is longer than 3 centimeters, your risk doubles. If it’s over 10 cm, your risk is more than 10 times higher than someone with short-segment disease.

- Low-grade dysplasia: This means the cells are starting to look abnormal under the microscope. Having it increases your risk of cancer by five times.

- High-grade dysplasia: This is the last step before cancer. At this stage, your annual risk of turning into cancer jumps to 23-40%.

- Smoking and obesity: Both make acid reflux worse and directly fuel abnormal cell growth. Abdominal fat pushes stomach acid up into the esophagus, while smoking damages the lining’s ability to heal.

- Acid exposure despite PPIs: If you’re on proton pump inhibitors like omeprazole but still have reflux symptoms, your risk of progression is 7.3 times higher. That means your treatment isn’t working well enough.

What doesn’t raise your risk? Alcohol. Surprisingly, some studies suggest that H. pylori infection - the bacteria that causes stomach ulcers - might actually lower your risk because it reduces stomach acid production. But that’s not a reason to go out and get infected.

How Is Dysplasia Detected?

Barrett’s esophagus can’t be diagnosed with blood tests or imaging scans. You need an endoscopy - a thin, flexible tube with a camera - and biopsies. But not just any biopsies. The standard is the Seattle protocol: taking four random biopsies every 2 centimeters along the length of the abnormal tissue. This cuts the chance of missing dysplasia by more than half.

Even then, diagnosis is tricky. Community pathologists agree on low-grade dysplasia only 55% of the time when compared to expert GI pathologists. That’s why many doctors recommend getting a second opinion from a specialist if dysplasia is found. Misdiagnosis leads to either unnecessary treatment or dangerous delays.

What Are the Ablation Options?

If you have confirmed dysplasia - even low-grade - your doctor will likely recommend ablation. This means destroying the abnormal tissue so healthy cells can grow back. There are three main methods, each with trade-offs.

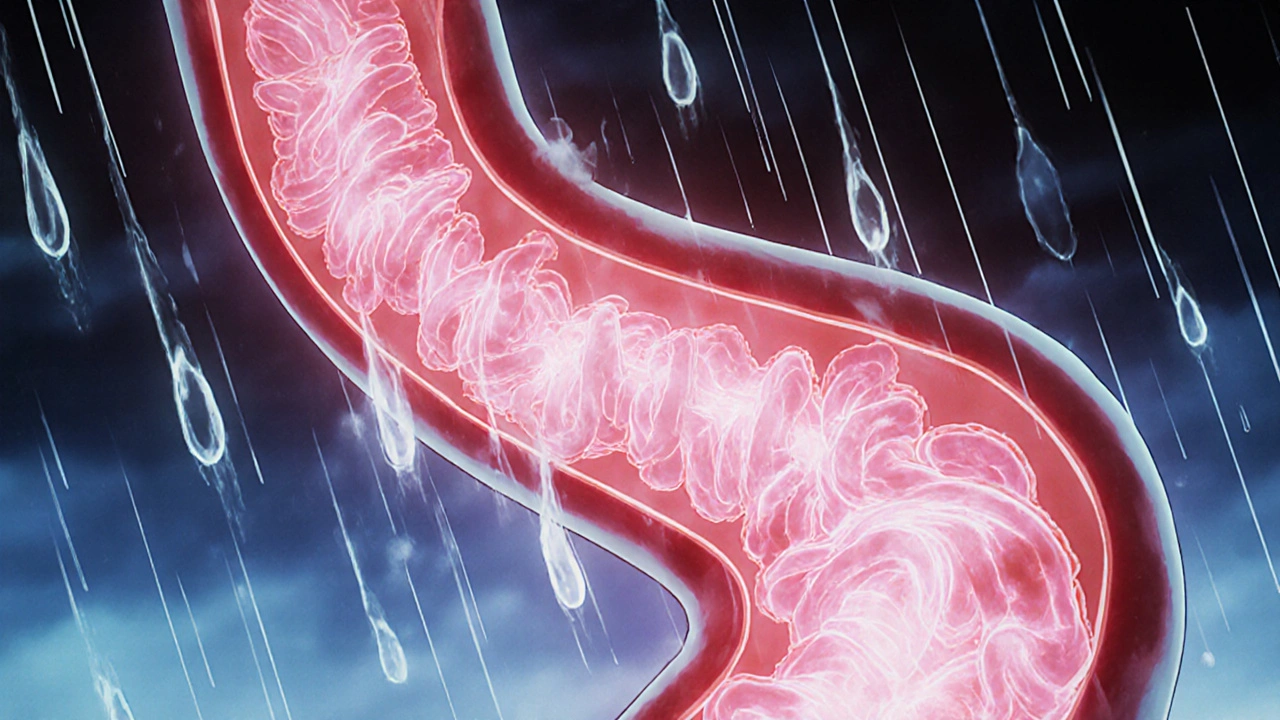

Radiofrequency Ablation (RFA)

RFA is the gold standard. It uses controlled heat delivered through a balloon or probe to burn off the abnormal lining. The HALO360 system treats the whole circumference of the esophagus; HALO90 targets visible spots. Studies show it clears intestinal metaplasia in 77-91% of cases and dysplasia in nearly 90%.

It’s not perfect. About 6% of patients develop strictures - narrowings in the esophagus that make swallowing painful. These often require dilation, sometimes multiple times. But compared to other options, RFA has the best track record for long-term results and lowest complication rate.

Cryoablation

Cryoablation freezes the tissue instead of burning it. Nitrous oxide is sprayed through a balloon to reach -85°C. It’s less likely to cause strictures (only 2-3% risk), which makes it a better choice for people who’ve had previous scarring or strictures. One trial showed 82% success in eliminating dysplasia.

It’s also easier to repeat if needed. But it’s slightly less effective at fully eradicating the abnormal tissue. One head-to-head study found RFA cleared metaplasia in 91.5% of cases versus 65% for cryoablation. It’s a good option, especially if you’re high-risk for scarring, but not the first choice for most.

Photodynamic Therapy (PDT)

PDT uses a light-sensitive drug and laser light to kill abnormal cells. It was used more in the 2000s, but now it’s rare. Why? It causes severe skin sensitivity to sunlight for weeks after treatment. It also leads to strictures in up to 17% of cases - much higher than RFA or cryoablation. Unless you have no other options, this isn’t recommended anymore.

Endoscopic Mucosal Resection (EMR)

EMR isn’t for widespread Barrett’s. It’s for visible lumps or bumps - early tumors or nodules - that might be cancerous. The endoscopist lifts and removes the lesion in one piece. Success rates are high: 93% for lesions under 2 cm. But it carries a 5-10% risk of bleeding and a 2% risk of perforation. It’s often combined with RFA afterward to clear any remaining abnormal tissue.

Cost, Access, and Real-World Outcomes

RFA costs about $12,450 per session. Cryoablation is cheaper at $9,850. But because RFA works better the first time, most patients need fewer repeat sessions. Over five years, the total cost per quality-adjusted life year is nearly identical: $38,200 for RFA versus $36,700 for cryoablation.

But here’s the problem: access isn’t equal. In academic hospitals, nearly all patients get ablation if they need it. In rural clinics, only 42% offer it. That means people in smaller towns are more likely to be monitored without treatment - and more likely to die from esophageal cancer. The CDC found mortality is 2.3 times higher in rural areas.

Real patient stories reflect this gap. One Reddit user described three RFA sessions costing $4,200 each, followed by four dilation procedures for strictures. “The pain during dilation was worse than the original Barrett’s symptoms,” he wrote. Another patient on a support forum said cryoablation cured her chronic cough - a symptom she didn’t even realize was linked to reflux.

What Happens After Ablation?

Ablation isn’t a cure-all. You still need lifelong monitoring. Even after all the abnormal tissue is gone, Barrett’s can come back. With high-dose PPIs (esomeprazole 40mg twice daily), recurrence drops to 8.3% at three years. With standard doses, it’s over 24%.

That’s why the new standard of care is: ablation + high-dose PPI + endoscopy every year for the first 3 years, then every 2-3 years if clear. And you still need to manage your reflux. Lose weight. Quit smoking. Avoid late-night meals. Elevate your head. These aren’t just “lifestyle tips” - they’re part of your treatment plan.

The Controversy: Are We Over-Treating?

Not everyone with Barrett’s needs ablation. In fact, most don’t. Only 10-15% of people with chronic GERD develop Barrett’s. And only a small fraction of those will ever turn into cancer. Yet Medicare data shows 25-30% of patients with non-dysplastic Barrett’s are getting unnecessary ablation.

Why? Because dysplasia is hard to diagnose. A 2020 study found community pathologists misclassified 45% of low-grade dysplasia cases. Some patients get labeled with dysplasia when they don’t have it - and then undergo painful, expensive procedures they don’t need.

That’s why guidelines now say: Only treat confirmed dysplasia. If you have non-dysplastic Barrett’s, stick with surveillance endoscopies every 3-5 years and aggressive reflux control. Don’t rush to ablation. The risk of cancer is too low to justify the risks of treatment.

What’s Next?

Technology is catching up. New AI tools can now spot dysplasia during endoscopy with 94% accuracy - better than most human endoscopists. In trials, these systems flagged lesions doctors missed. And blood tests for molecular markers like TFF3 methylation could soon tell us who’s truly at risk - without needing a biopsy.

The FDA approved a new cryoablation system with real-time temperature control in 2023. A new RFA device for longer Barrett’s segments is expected in 2024. These aren’t just upgrades - they’re steps toward making treatment safer, more precise, and more accessible.

The goal? Reduce esophageal cancer deaths by 45% by 2035. That’s possible - but only if we get better at identifying who needs help, and make sure everyone gets it, no matter where they live.

Can Barrett’s esophagus go away on its own?

Rarely. In less than 1% of cases, the abnormal tissue reverts to normal without treatment, usually after major lifestyle changes or after long-term acid suppression. But you can’t rely on this. Without monitoring or intervention, the risk of cancer still exists. That’s why even if symptoms improve, regular endoscopies are essential.

Do I need to stop taking my PPI after ablation?

No. In fact, you’ll likely need to keep or even increase your dose. Studies show that continuing high-dose proton pump inhibitors (like esomeprazole 40mg twice daily) after ablation cuts the chance of Barrett’s returning by more than half. Ablation removes the abnormal tissue, but it doesn’t fix the underlying acid reflux. If acid keeps coming up, the cells can turn abnormal again.

Is cryoablation better than RFA for someone with a history of strictures?

Yes. If you’ve had previous esophageal strictures or scarring, cryoablation is often preferred. It causes less tissue damage and inflammation, reducing the risk of new strictures to under 3%, compared to 6-8% with RFA. For these patients, the slightly lower success rate is worth the safety advantage.

Can I still drink coffee if I have Barrett’s esophagus?

Moderation matters. Weekly coffee consumption has been linked to a higher risk of progression in some studies. But it’s not the caffeine itself - it’s how it relaxes the lower esophageal sphincter, letting acid reflux up. If you drink coffee daily and have worsening reflux, cutting back or switching to decaf may help. But if you tolerate it well without symptoms, it’s not a strict no.

How often should I have an endoscopy after ablation?

After successful ablation, you’ll need an endoscopy every year for the first 3 years. If no Barrett’s tissue comes back, then every 2-3 years after that. Even if you feel fine, skipping follow-up is risky. Recurrence can happen without symptoms, and early detection is what saves lives.

Is Barrett’s esophagus hereditary?

Yes, there’s a genetic component. If a close family member has Barrett’s esophagus or esophageal adenocarcinoma, your risk increases by 23%. This doesn’t mean you’ll definitely get it, but it does mean you should be screened earlier - especially if you also have chronic GERD. Talk to your doctor about starting endoscopies in your 40s if you have this family history.

Can weight loss reverse Barrett’s esophagus?

Weight loss alone won’t make Barrett’s disappear, but it can dramatically lower your risk of progression. Losing even 10% of your body weight reduces acid reflux and inflammation in the esophagus. One study showed that obese patients who lost weight had a 50% lower chance of developing dysplasia over five years. It’s not a cure, but it’s one of the most powerful tools you have.

Chris Taylor

November 29, 2025 AT 12:44Man, I never realized how silent this stuff is. I had heartburn for years and just thought it was stress. Got diagnosed with Barrett’s last year and honestly felt like a bomb went off. Thanks for laying it all out like this.

Melissa Michaels

December 1, 2025 AT 03:06It's critical to emphasize that surveillance endoscopy remains the cornerstone of management for non-dysplastic Barrett's. Ablation should never be pursued without confirmed histology. Many patients are over-treated due to misinterpretation of low-grade dysplasia by non-specialist pathologists.

Nathan Brown

December 1, 2025 AT 05:12It’s wild how we treat the body like a machine you fix with lasers and drugs, but ignore the root - the way we live. We eat late, stress out, sit all day, then wonder why our esophagus turns into a science experiment. Ablation fixes the symptom, not the story. What if the real cure is slowing down? Not burning or freezing tissue… but healing the rhythm of life?

And yet… we keep rushing to the next procedure. Like the body’s just a car with a broken part. Maybe it’s not broken. Maybe it’s screaming.

Matthew Stanford

December 2, 2025 AT 22:01Good breakdown. RFA is the go-to for a reason. But if you’ve had prior strictures or are worried about scarring, cryoablation is totally worth considering. Less pain, less risk. And if you’re in a rural area without access to specialists, just getting monitored is better than nothing.

Olivia Currie

December 4, 2025 AT 18:11OMG I JUST HAD CRYOABLASTION AND MY COUGH IS GONE?? Like, I didn’t even know I was coughing all the time until it stopped. I feel like a new person!! Also I cried during the procedure and the nurse gave me a cookie after 😭🍪

Curtis Ryan

December 5, 2025 AT 18:54So i got barretts last year and did rfa and now i got strictures and had 4 dilations and wow like the pain was insane but worth it?? I lost 30 lbs and quit smoking and my reflux is way better now. Just dont skip the followups!!

Rajiv Vyas

December 6, 2025 AT 12:03They say ablation saves lives but who really benefits? Big Pharma? Hospitals? I’ve seen the bills. You get scanned, burned, dilated, then billed for the ‘follow-up anxiety’. Meanwhile the real cause? Corporate food, corporate medicine. They want you dependent. You think your esophagus changed because of acid? Nah. It changed because your whole system’s poisoned.

farhiya jama

December 7, 2025 AT 17:07Ugh. Another long medical post. Can we just talk about something fun? Like cats or TikTok? This gives me a headache.

Astro Service

December 7, 2025 AT 22:26Why are we letting foreigners tell us how to treat our own bodies? We’ve got the best doctors in the world. Why are we using some new cryo thing from Europe? Stick with RFA. American tech. American results. No more foreign experiments on our esophagus.

DENIS GOLD

December 9, 2025 AT 01:50Oh great. Another ‘you’re gonna die if you don’t get burned’ scare post. Next they’ll tell me coffee gives you cancer. I’ve been drinking espresso since I was 14 and I’ve never had a problem. Maybe the real problem is doctors who make money off fear.

Ifeoma Ezeokoli

December 9, 2025 AT 16:59My cousin in Lagos got diagnosed with this and couldn’t even get an endoscopy. They told her to drink ginger tea. I cried reading this. Access isn’t just a US problem. This isn’t just medical - it’s justice.

Daniel Rod

December 10, 2025 AT 08:37Just had my 3rd RFA last month. Still on esomeprazole 40mg twice. Still elevating my head. Still avoiding pizza after 7pm 😅 But I’m alive. And that’s the win. Thanks for the reminder - this isn’t just a procedure. It’s a lifestyle. 🙏

gina rodriguez

December 10, 2025 AT 22:21I’m so glad you mentioned the importance of continuing PPIs after ablation. So many people think once it’s gone, they’re done. But acid doesn’t just disappear. Keep treating the root - not just the symptom.

Sue Barnes

December 11, 2025 AT 20:26People who don’t get ablation are just gambling with their lives. If you have dysplasia and you’re not treating it, you’re being reckless. Stop making excuses. This isn’t a lifestyle choice - it’s a medical emergency.